ESnet Veteran Joe Metzger Retires, Having Helped Build ESnet3 through ESnet6

By Bonnie Powell

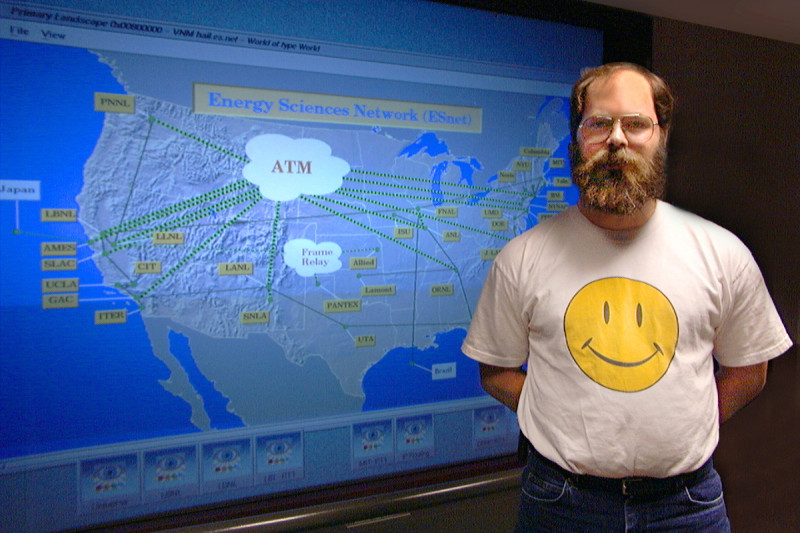

Joe Metzger in 1997, on a visit to Berkeley Lab not long after he was hired as ESnet’s first fully remote employee

Decades before the COVID-19 pandemic normalized remote work and turned Zoom into a global juggernaut, Energy Sciences Network (ESnet) employees have been telecommuting. Back in January 1997, when Joseph Metzger joined ESnet, 60% of ESnet employees were already doing so one to three days a week from the dedicated “teleworking center” in Livermore, California, set up for Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) employees after the National Energy Research Supercomputing Center (NERSC) moved to Berkeley the year before. However, Metzger was ESnet’s first full-time remote employee. The plan was for him to videoconference from an office at Ames National Laboratory in Iowa and travel to the Bay Area regularly for in-person meetings.

Metzger at the April 2024 ESnet Site Coordinators Committee Meeting, where he presented on the Site Resiliency Program he created and led.

The experiment was successful. After more than 27 years as a senior engineer with ESnet, Metzger retired June 27. His tenure encompasses the progression of the Department of Energy’s data circulatory system from ESnet2 to ESnet6; ESnet’s expansion across the Atlantic, into Europe; and its evolution from a fast and reliable network services provider to the innovative, multifaceted global research & education leader it is today. And throughout those two-plus decades, this outspoken, impressively bearded Midwesterner — for whom “formal wear is a plaid shirt,” as one colleague puts it — has made key contributions to ESnet’s mission of accelerating scientific research around the globe.

“Not only has Joe been an amazing engineer, but he’s also been a very supportive guide,” says ESnet Executive Director Inder Monga, who joined ESnet 17 years after Metzger. “During my early years at ESnet, Joe would always make time to explain why things were a certain way. The wide range of his contributions to ESnet, from systems to network architecture, has been remarkable. I wish him all the best in the next phase of his life, and we will miss him and his expertise dearly.”

The Accidental Network Engineer

Raised in a Minneapolis suburb, Metzger first became interested in computers in high school, when he first encountered an Apple II. He enrolled at St. John University in Minnesota thinking he’d major in physics; challenges with calculus and a work-study job at the PC center led him to switch to computer science. He transferred to the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire for his junior year and finished his B.S. there. His first job out of school was in Washington, D.C., working for a defense contractor. In addition to collecting and visualizing data, developing prototypes, and doing some systems management, around that time, he had his first introduction to networking, managing a Cisco AGS+ router as a Control Data employee working on a military base.

"People are sometimes mentors without intending to be, and Joe has been one for me. He would say to me, ‘You haven’t thought this through properly.’ That instilled a lot of discipline in me.”

—Michael Sinatra

After a few years, however, he and his wife, Laura, were ready to move back to the Midwest to be closer to their families as they started their own.

Metzger went to the library to look at newspapers’ classified job ads. “I saw one for systems manager at Ames National Laboratory, and I had no idea where Ames was — just that it was somewhere in the Midwest,” he recalls. Ames Lab turned out to be located on the campus of Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. He landed the job, and he and Laura have lived in this university town since 1992, raising three children (now all grown).

Ames was connected to other DOE labs via the then-nascent Energy Sciences Network, formally created in 1986. Both organizations’ staff were already involved with SCinet, the group of volunteers who build (and tear down) a temporary research network every year for the SC supercomputing conference. In 1994, Metzger’s Ames Lab supervisor, Steve Elbert, was the SCinet chair, and Metzger participated as well — getting to know and working closely with Berkeley Lab networking staff, including some from ESnet.

Metzger actually applied for an opening at ESnet (and another at NERSC) at Elbert’s request, to gather salary information for a job reclassification effort. To his surprise, ESnet offered him the job. He turned it down, but ESnet just kept sweetening the deal — and he kept saying no thanks. Even though he was flattered, “I never really considered moving to California,” he says. At last, when they said he could telework, he agreed. In a gentleman’s agreement, Elbert let him keep an office at Ames down the hall from his old one.

“A Head in a Box”

Metzger started as an engineer in the Network Information Services Group. “I really wanted to be in Network Engineering, but they didn't have any openings at the time I applied,” he explains.

Joe's daughter Sara tagged along for a 2006 perfSONAR meeting in Cambridge.

His first big project was splitting the ESnet and NERSC email systems, then updating ESnet’s, deprecating the X.400 system. Fittingly, he was also heavily involved in the ESnet videoconferencing scheduling system. (Watch the 1996 news broadcast about ESnet, “The Future of Work is Remote.”) In addition to its internal usage, ESnet ran a video conferencing service for all the DOE labs, known as the ESnet Collaboration Service, over its ESnet2 backbone.

At first this was confined to specialized videoconference rooms, but soon many ESnet employees had dedicated videoconferencing monitors on their desks, such as Tandbergs. “We would just hang out on video all day, like in a watercooler chat,” recalls Chin Guok, now ESnet’s Chief Technology Officer, who joined ESnet a month after Metzger. “That’s how I met and got to know Joe — as a talking head, a head in a box.”

During Joe’s first decade and a half at ESnet, he went back to school part time, at Iowa State, completing his master’s in computer engineering in 2006. That year he also assisted with the upgrade from ESnet3, which was about building predictable network services using QoS and MPLS-TE and launching ESnet’s On-Demand Secure Circuits and Advance Reservation System (OSCARS), to ESnet4, which focused on deploying purpose-built architectures such as the ScienceDMZ and perfSONAR measurement tool.

But most importantly, during this time he began building the human networks that would lead to one of his greatest contributions to ESnet: its trans-Atlantic expansion.

“Joe’s Solution”

By 2005 CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics, was producing an enormous amount of data from its ATLAS, CMS, and ALICE experiments. “It was widely recognized that the U.S. and European high-energy physics (HEP) data traffic was going to rapidly swamp the general R&E trans-Atlantic network capacity — a single 10 Gigabit Ethernet circuit,” explains William Johnston, then ESnet’s executive director. (There were others, but they all had policy restrictions.)

"I have always appreciated Joe's ability to disambiguate or ‘un-confuse’ situations. It's a superpower, being able to ask the right clarifying question at the right time.”

—Chris Tracy

A committee made up of ESnet, Internet2, CERN, GÉANT, and other R&E stakeholders was formed to recommend an approach. They met for several years but failed to agree on an acceptable solution.

Finally, at the end of a long, contentious meeting in Washington, D.C. in 2010, “Joe got up and went to the whiteboard. He said, ‘Why don’t we just use a Layer 3 Virtual Private Network overlay that only the HEP community has access to? This is a technology that we can all support, and we understand how to administer it. And it allows each network to incorporate and remove circuits at their discretion,’” recounts Johnston.

Miraculously, all parties agreed to what became known as “Joe’s Solution” — a name that stuck until David Foster at CERN proposed the current one: LHCONE (for Large Hadron Collider [LHC] Open Network Environment). Today, LHCONE is a global network connecting more than a hundred HEP sites around the world, and ESnet carries hundreds of petabytes of data per year to and from CERN and its U.S. collaborators.

Submarine Dreams

Metzger (center) with Phil Demar from FERMI and Dale Finkelson from Internet2 at a LHCOPN meeting in Paris in 2013

ESnet is able to transport those massive LHC data sets thanks to another achievement of Metzger’s: its trans-Atlantic branch, whose working title was ESnet European eXtension (EEX) and which was completed around 2013.

Back in 2006, ESnet had no circuits to Europe. The U.S. HEP community, comprising U.S. universities and DOE national labs such as Brookhaven and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, was running its own ad-hoc, trans-Atlantic network to access CERN. But with the LHC coming online in less than two years, “they decided that they needed a more professionally run, reliable network,” says Johnston. ESnet was asked to draft a proposal for an extension of the ESnet backbone to Europe that would provide the same level of reliability as its terrestrial network — greater than 99.9% availability around the clock, 365 days per year – despite relying on submarine cable systems, which are vastly different from terrestrial optical fiber–based systems. They fail much more frequently, cut by ship anchors and fishing equipment, and the time to repair can range from weeks to months depending on the weather.

ESnet’s proposal was approved, and DOE’s High Energy Physics program agreed to fund it for the first few years, then ASCR would step in. Metzger led the effort to translate this general architecture into a detailed engineering design, complete with a reliability analysis that took into consideration the need for resiliency, given the challenges of submarine cable systems, and oversaw its deployment. The past decade’s smooth, uneventful performance of the LHC experiments and LHC Data Challenges are testament to the success of Metzger’s efforts.

“Joe is a creative and methodical engineer,” says Johnston. “Once he has come up with a design, he carries it through to implementation — testing and correcting initial assumptions as needed.”

As part of the trans-Atlantic networking project, ESnet agreed to station an engineer at CERN for the first three years. Metzger took the third appointment, in 2016, moving overseas just after his last child graduated from high school. “It was great to see in person how another large lab operated!” he says. “Just living in a foreign country, living in a city, and then taking long-weekend trips to different countries and cultures every month. It was a bit of a culture shock, but in a good way.” (Read GEANT’s 2017 interview with Metzger about his year in Geneva.)

Metzger hiking in Switzerland during his year at CERN, with the Matterhorn in the background.

Planning and Architecting ESnet’s Future

The trans-Atlantic networking project was a significant milestone in the expansion of ESnet’s focus under successive executive directors. In 2016, Metzger pushed for the formation of a Network Planning Team, whose initial vision was to “ensure that the ESnet network and the services it provides enable our users to effortlessly collaborate on some of the world's most important scientific challenges” — a close precursor to ESnet’s vision today. Metzger was the first lead of Network Planning, which comprised Guok, Chris Tracy, and Nick Buraglio. (It soon morphed into the formalized Planning & Architecture Group, which Tracy now leads and in which Buraglio remains; PAG is part of the Planning & Innovation Department, led by Guok.)

ESnet5 had been completed five years earlier, and the Network Planning team was thinking about ESnet6. Previous iterations had been about being bigger, faster, more reliable. ESnet6 would be a “clean-sheet design,” in which ESnet was free to start with a blank sheet of paper, ignore what existed, and focus on building a network that would be able to not only accommodate but accelerate global, big-data scientific research over the next decade. Because of the project’s size and cost, it would also be subject to DOE’s 413.3B requirements for oversight and review — a much more rigorous process than had been applied to previous iterations.

Guok led the design phase of ESnet6, resulting in a 200-page architectural blueprint, and Metzger was entrusted with leading its refinement and implementation. “In a blueprint, you’ll see ‘window.’ But what exact kind of window? Does it open in or out?” Guok explains. Metzger translated the blueprint strategy and requirements into complex vendor procurements and hundreds of timelines, calculated traffic engineering needs, and calibrated necessary levels of redundancy and resiliency. He flew out for the many 413.3B reviews that went late into the night.

And in October 2022, ESnet unveiled ESnet6, the most sophisticated, innovative iteration of the DOE’s premier scientific research network yet — within scope, under budget, and ahead of schedule.

Metzger is quietly proud that “ESnet managed to overdeliver on all three, even while COVID was happening, which just threw a whole wrench in the works. There were just a million and one moving parts. Trying to figure out what was going to happen when, what’s going to get hung up by what, and eliminating interdependencies as much as possible was a challenge” — even before factoring in the disruptions to collaboration and supply chains caused by a global pandemic.

A Legacy of Discipline

ESnet6 was a huge achievement, and Metzger was a key contributor. “Joe is practical and detail oriented. He brings incredible focus, which can make him a pain to work with sometimes — but he’s usually right,” says Guok.

Although “outspoken” is a descriptor used by many of Metzger’s longtime colleagues, it is a strength they all appreciate. “He won’t hold back. However, if he’s being vocal about something, it’s because he understands it well, and that makes him worth listening to,” says Tracy. “I have always appreciated Joe's ability to dis-ambiguate or ‘un-confuse’ situations. It's a superpower, being able to ask the right clarifying question at the right time. He's also always still open to other people’s ideas.”

According to ESnet veteran Michael Sinatra, a network engineer who worked closely with Joe on ESnet6, “Joe does not sugarcoat things, but he has softened and learned how to pitch things better. People are sometimes mentors without intending to be, and he has been one for me. He would say to me, ‘You haven’t thought this through properly,’ or ‘You should have asked that question six months ago.’ That instilled a lot of discipline in me and greater maturity in how I approached the tasks I had to do.”

Metzger announcing his retirement at ESnet’s All-Staff retreat in January.

Overall, his colleagues agree, Metzger also leaves the engineering side of ESnet a more rigorous place, with more structure, clearer roles and responsibilities, and better planning.

That makes Metzger sound like he’s always quite serious, which is not the case. He surprised everyone at ESnet’s all-staff retreat in January by announcing his retirement at the end of his “Getting the Most Out of Your LBL Career” lightning talk, via the cover of “So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish,” from Douglas Adams’ famous Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy series.

He and Laura, who also just retired, won’t be hitchhiking, just hiking around the U.S. and Europe — they want to explore “more beaches, more mountains, and more woods,” says Metzger. For a man who many will remember with admiration for his careful planning, retirement offers the intoxicating promise of the “freedom to get up and go whenever you want to, no constraints or need to plan far in advance.”