From UNIVACs to ESnet, John Christman’s Retiring from the Leading Edge of Technology

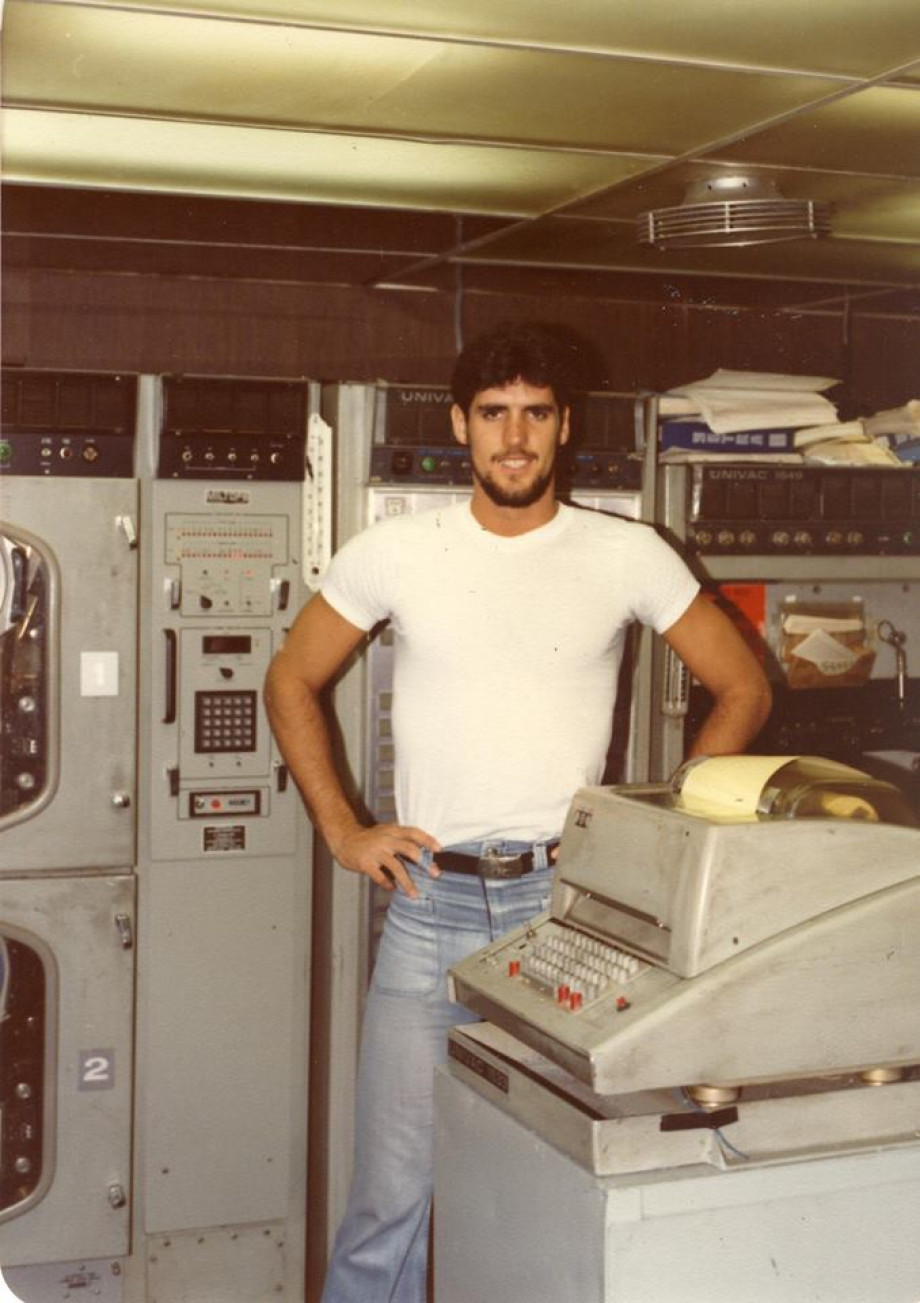

John Christman's introduction to advanced technology began on board the U.S.S. Dixie, where he maintained a UNIVAC computer.

Contact: Jon Bashor, jbashor@lbl.gov, 510-486-5849

When John Christman enlisted in the U.S. Navy the day after his 18th birthday, he was hoping to work as either a welder or machinist. But he scored too high on the skills assessment and instead ended up studying advanced electronics. It was one of those twists of fate that set his whole career in motion. On June 29, Christman will leave the lab after 29+ years, the last 10 as a network engineer with ESnet.

He started out with two years of electronics school in the Navy, going to class eight hours a day and learning about vacuum tubes, transistors and programming. And while the technology changed, the nature of Christman’s work remained constant – understanding and maintaining systems to ensure that users were able to reliably get the information they needed.

“Every year you learn something new – that’s what I love about the lab,” he said. “You’re always at the cutting edge, nothing gets stale.”

After completing his Navy training, Christman was assigned to the U.S.S. Dixie, a destroyer tender, essentially a floating repair shop that repaired other ships at sea. All of the Dixie’s records – payroll, repair job tracking, parts and labor needed and more – were tracked by an on-board UNIVAC computer. It had 18 bit words of core memory, 64K of extended memory and hummed along at 1 MHz.

“You have way more power in your cell phone and this thing was as big as a refrigerator – all transistors and core memory,” Christman said. “The fun part was troubleshooting it, looking for a bad transistor or broken wire.”

The machine tended to act up if the temperature went above 70 degrees or if it was powered up and down too often. “There were no boards to swap out – you had to use an oscilloscope. If it broke hard, it was easy to fix, but if one of the 5-volt transistors was choppy and failed once a day, it was a bear to find.” Christman recalled spending a four-day Thanksgiving weekend tracking down a failing transistor, finally finding it Sunday night. While his shipmates were on leave, he was stuck on board until he fixed the problem.

Getting into Networking

When he was discharged in 1980, he considered taking the test to be a firefighter. “I didn’t think there would be much computer work,” he said. But then he saw an ad for UNIVAC technicians to work at Western Union.

At the time, Western Union ran a telex network which allowed businesses to send information across the country and around the world. The company also operated the TWX service, which used the public telephone network to send messages. It all ran over 9600 baud links, or 9600 bits per second. “That was really smokin’ back then – most people were using 300 baud modems,” Christman said. He worked at 730 Market St. in San Francisco, “a huge hidden computer center with rows and rows of mainframes and tape drives.”

His hardest task at Western Union was fixing a memory unit that had been down for months. Three teams had already tried their hands, to no avail. Christman read all of their notes, then decided to remove the cover bearing a “DO NOT REMOVE” label. Armed with his scope, he found that the timing chain was slightly off – buy 5 nanoseconds. He tweaked it and the system was back on line.

Making the move to Berkeley

When Western Union shut the facility in 1987, Christman and a colleague landed interviews at the lab. After a two-hour interview in which he was “asked all kinds of questions,” Jim Greer of the Real Time Systems Group told him, “Let me show you where you’ll be working.” Christman figured that meant he got the job.

At the time, most of the research units at the lab had their own computer systems for controlling experiments at the Bevatron, the 88-inch cyclotron, the Super HILAC (Super Heavy Ion Linear Accelerator)and the 184-inch cyclotron, which was just shutting down to make way for the Advanced Light Source.

Christman worked mainly on ModComps, or modular computers, which were deployed to control the magnets, gates and other components of the accelerators. “It was kind of fun, except when they went down and you had all these physicists coming up to you every 15 minutes and asking, ‘When will it be fixed?’”

During his 10 years with the group, Christman said he never received formal training, but was just handed the manual and learned on the job. “We worked on everything from these big hammer drive printers to these old tape drives,” he said. “One time I worked on the oldest tape drive I’d ever seen, but fortunately they were pretty much all the same.”

As a member of LBLnet, John Christman(left) works with intern DeAndre Beswith (center) and Al Early.

But he could see that the old equipment was going away and that his job could, too. When NERSC moved from Lawrence Livermore to Berkeley Lab in 1996, Christman applied for a job, but didn’t get it.

“I saw that the Internet was going to be a big thing, so I applied for a job and was hired by LBLnet,” he said. “I downloaded Mosaic and manuals to study and learned html. One night I was communicating with a guy in Australia and asked how it was happening and he said ‘It’s the Internet.’”

Casting a Wider Net

Christman spent 10 years with LBLnet, often providing networking support for Berkeley Lab’s booth at the annual SC conference and in 2002 participated in one of the very first demonstrations of moving science data over a 10 Gbps network. In 2006, he joined ESnet.

“I’d done all I could do with the LAN, so I went to ESnet to learn about the WAN,” he said. “It was a higher speed network, with more routers.”

He got there just as ESnet-4 was starting. The network consisted of two 10 Gbps rings, one for IP traffic and one for science data.

The highlight for him was helping build ESnet-5, the 100 Gbps network that is the fastest science network in the world. “We moved to a new router platform and we lit our own dark fiber. And now we’ve built a 400 Gbps network between the lab and the old NERSC facility in Oakland.”

And while Christman has made it a point to always stay on top of changing technology, come June 29, he’ll be focusing his attention elsewhere.

“We’re going to travel – we’re going to Hawaii right off the bat,” he said. “Then to Oregon to get my golfing in.”

Over the years, Christman has hosted a number of Lawrence Livermore employees, renting them a room in his house which is near the lab. And he’s stayed in touch with many of them. Next summer, he and his wife will travel to Spain to attend the wedding of one former housemate, for example.

And then there is Christman’s all-consuming interest in grilling. He has shelves of trophies and boxes of ribbons for his steak recipes and ribs. At the Alameda County Fair, his steak topped with a whiskey-peppercorn sauce won top honors in the Beef is King competition (recipe below!). He’s now entering rib contests as a member of the Livermore Smokin’ Kings.

“One of my next purchases is going to be a grill that I can tow to various events,” he said. “Cooking’s a real passion of mine.”

As a final bookend to his 29 years at the lab, John Chrisman posed wth NERSC's Edison supercomputer.

John Christman's Whiskey Peppercorn Steak

Ingredients

- 2 tsp. fresh cracked black peppercorns

- 1 Tbsp. black, pink & green peppercorns

- 1/2 cup heavy cream

- 1/2 cup favorite whiskey (Jack Daniel's works best)

- 1" to 1-1/2" thick beefsteak of your choice

Some chunks of mesquite or oak wood along with charcoal for the fire.

Preparation

Marinate steak with olive oil and press in kosher salt and cracked black pepper and allow to sit for 1 or more hours. Start the coals and don’t start until the fire is at a good glow and not not much smoke coming from charcoals and wood. Heat a heavy skillet to high temperature. Sear steak quickly (20 sec. or so) on both sides to seal in juices then remove to grill for finishing to desired doneness. While steak is cooking on the grill, deglaze pan with 1/4 to 1/3 cup wine. (If there is little or no drippings from the steak add a little butter to the hot pan and brown but do not burn it, then deglaze). Add cracked black pepper, green peppercorns and 1/4 to 1/3 cup heavy cream to pan. Cook over medium heat, stirring constantly until liquid is reduced by half. By this time the steak should be done. Place steak on serving dish and pour pepper sauce over the steak or serve the sauce